The Metallurgical Ouroboros

Stephen Cornford / Caroline Jane Harris / Samantha Lee / Victor Seaward / Rustan Söderling

21st September to 21st October 2018

Part of Deptford X (21st - 30th September - www.deptfordx.org)

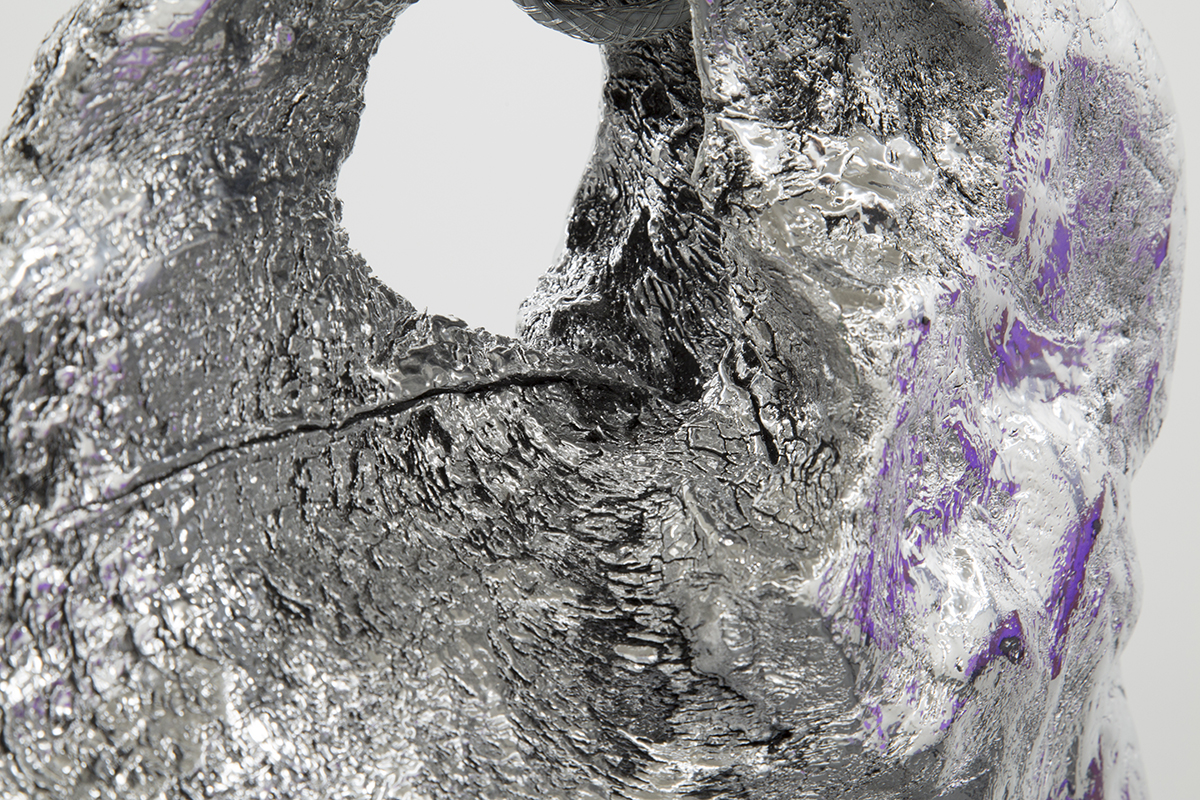

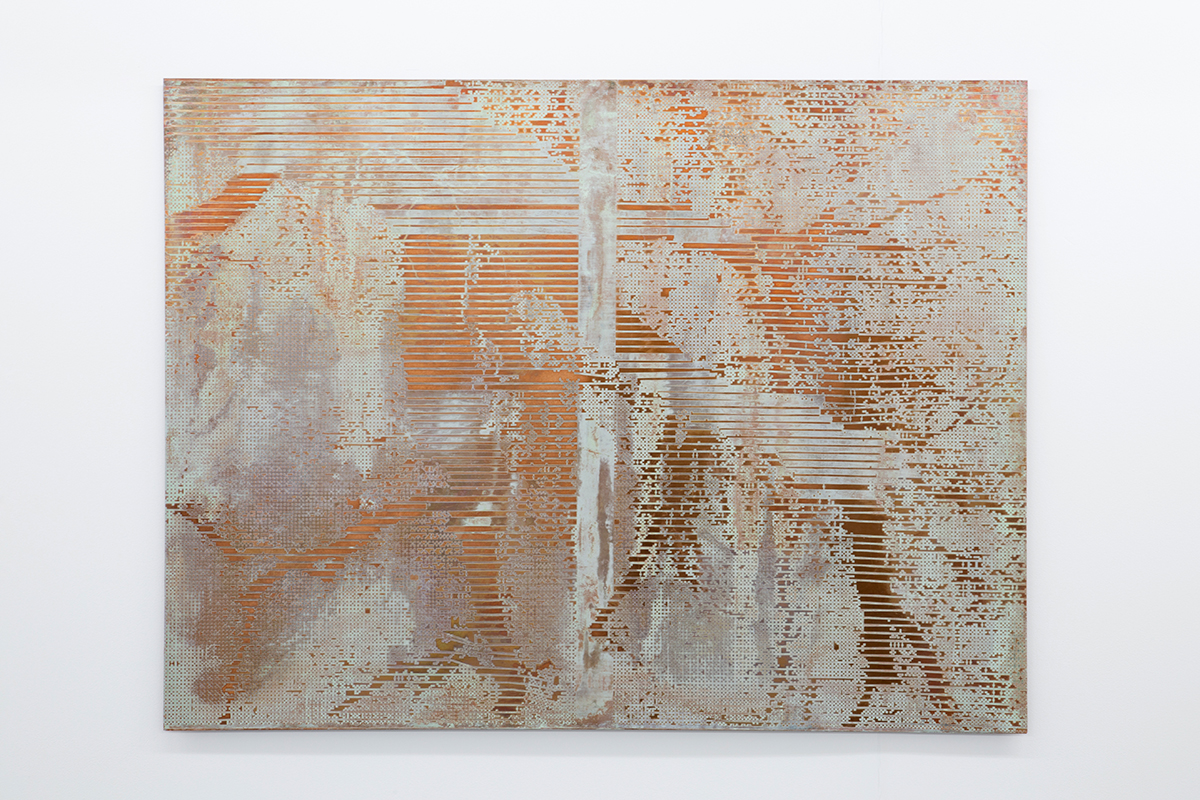

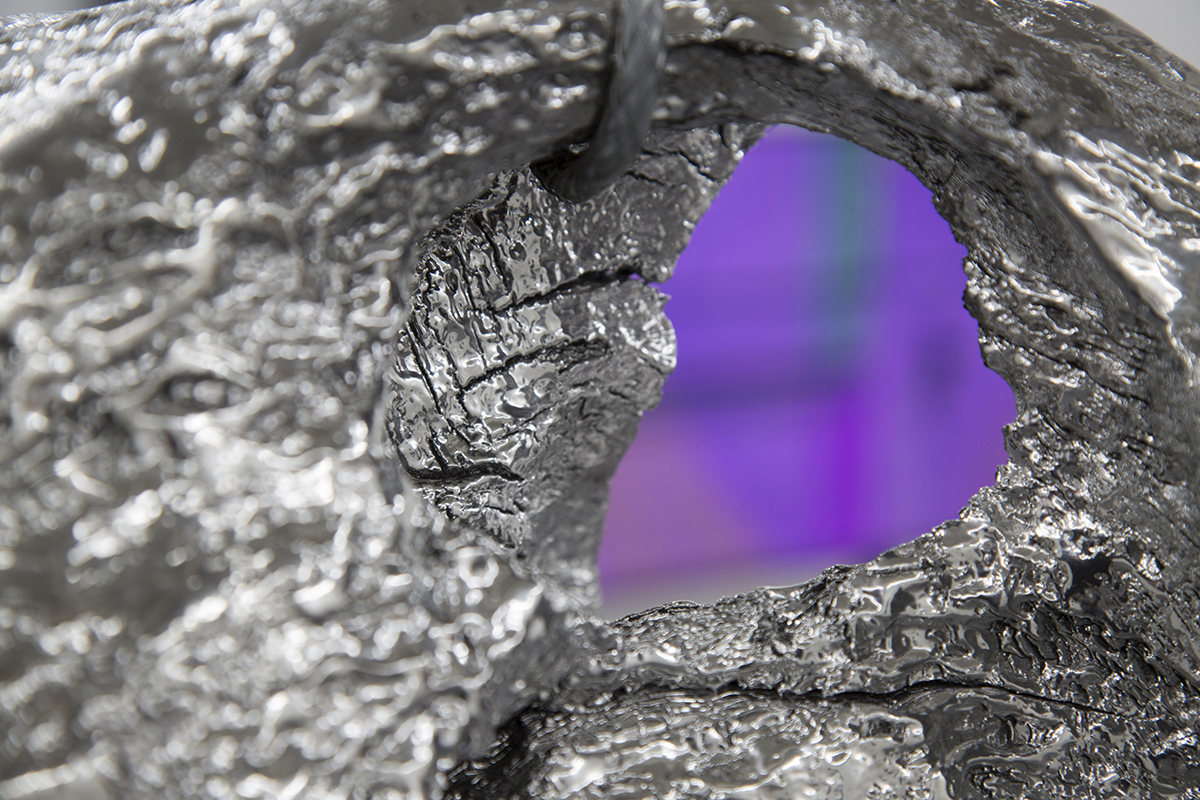

The Ouroboros is a symbol that can be found across ancient culture, depicting either a snake or dragon consuming its own tail. It represents the continuous circle of life and the eternal emancipation of living networks and ecosystems; with the dragon being the most primordial symbol representing the class of all predators, mastering fire [destruction] and hording gold [wealth]. The qualities of the animal kingdom have long inspired the design of materials and machines through bio-mimetics, as the materiality of technology is bio/geo-logical and nature is fully intertwined in processes of both its production and consumption. The nature of transmutation sees the technological artifact becoming the philosopher’s stone - the archetypal symbol of alchemy - turning base metals and minerals into a new gold.

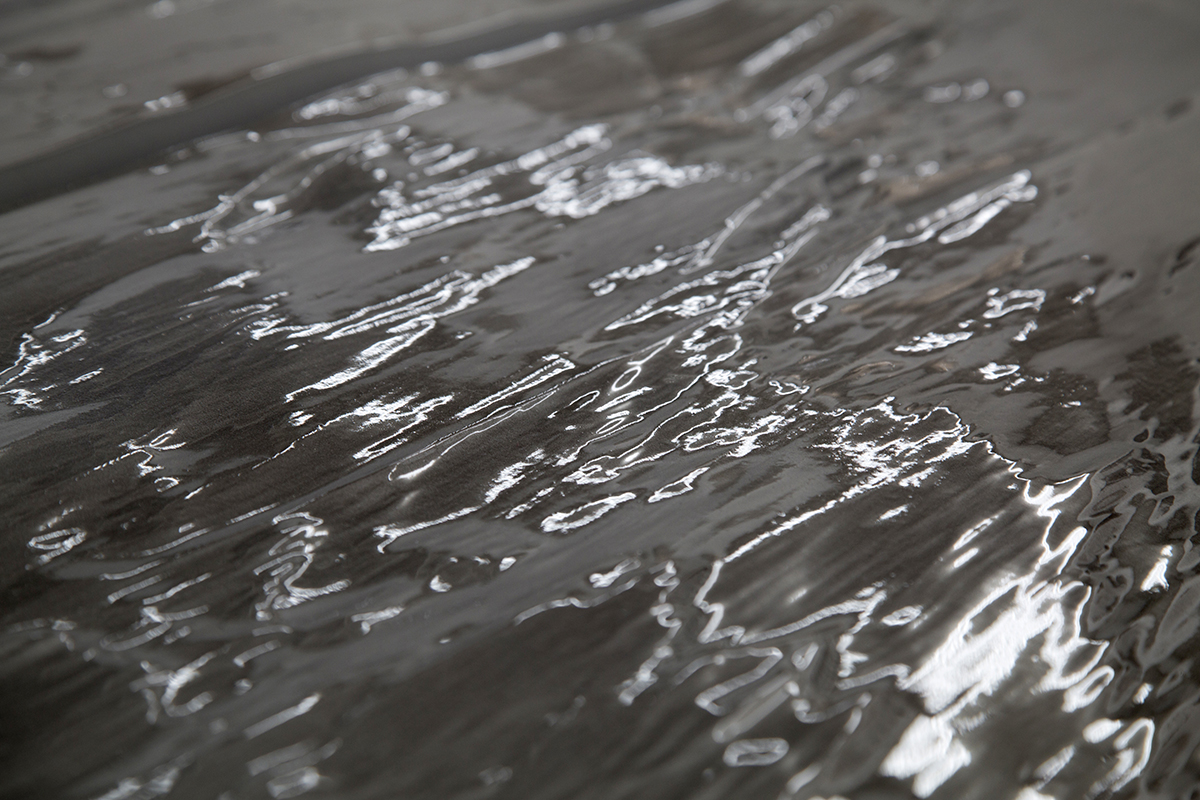

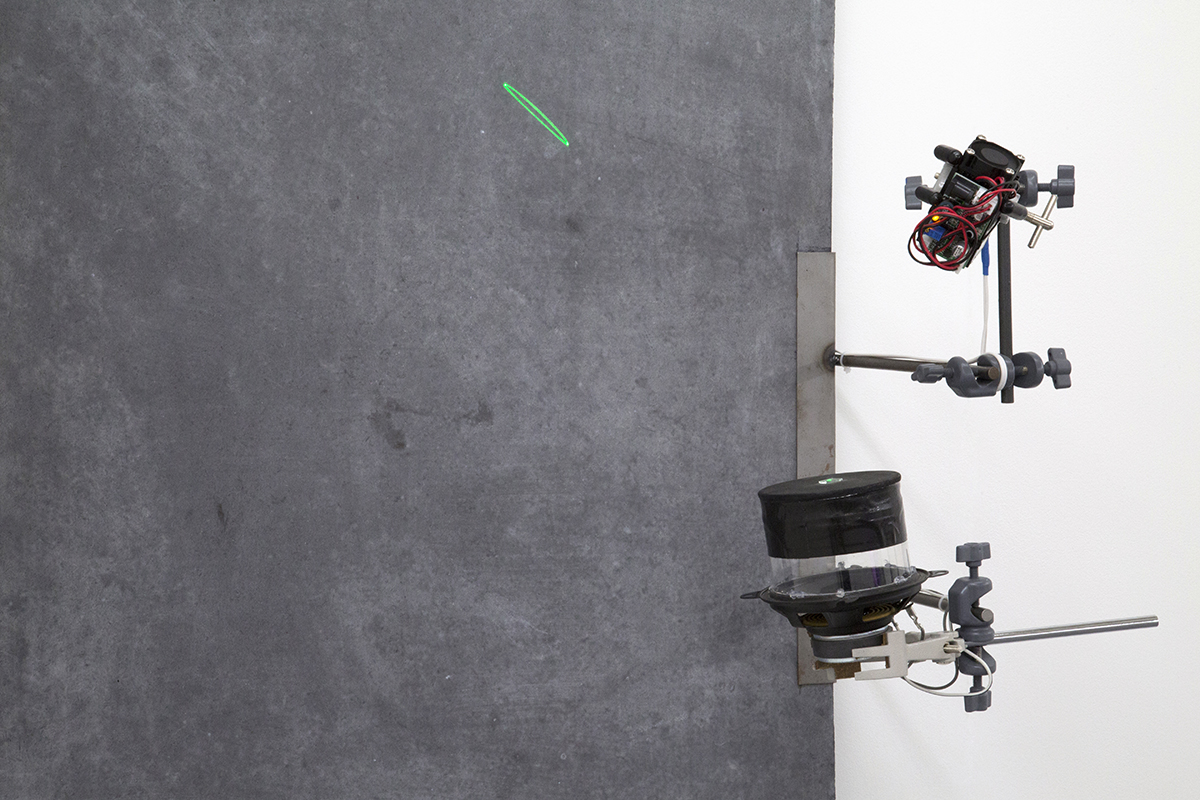

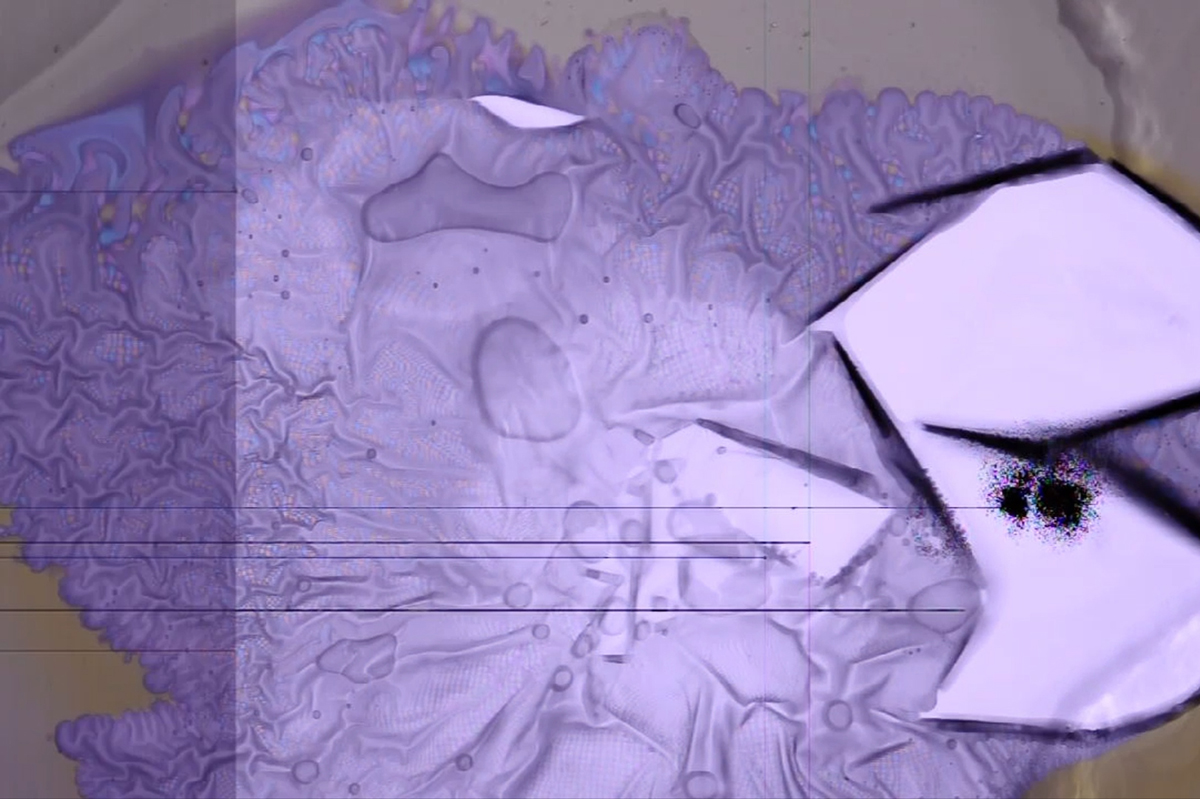

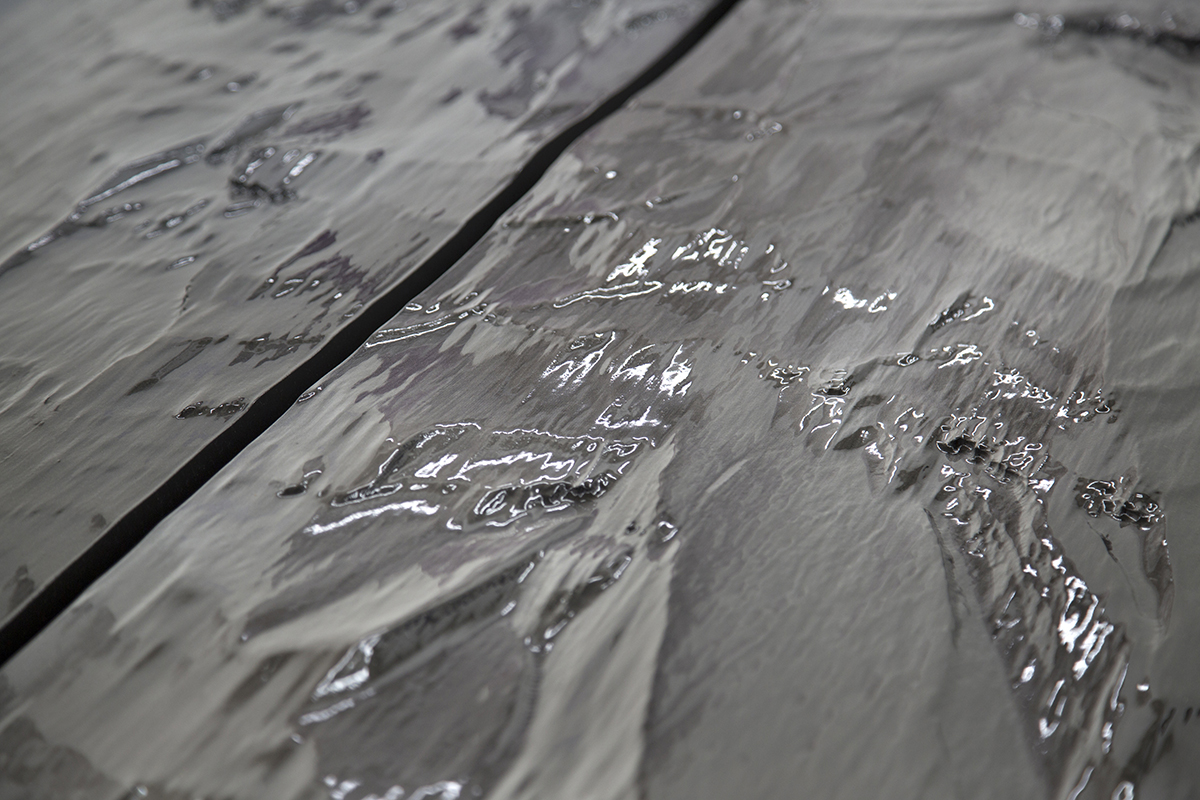

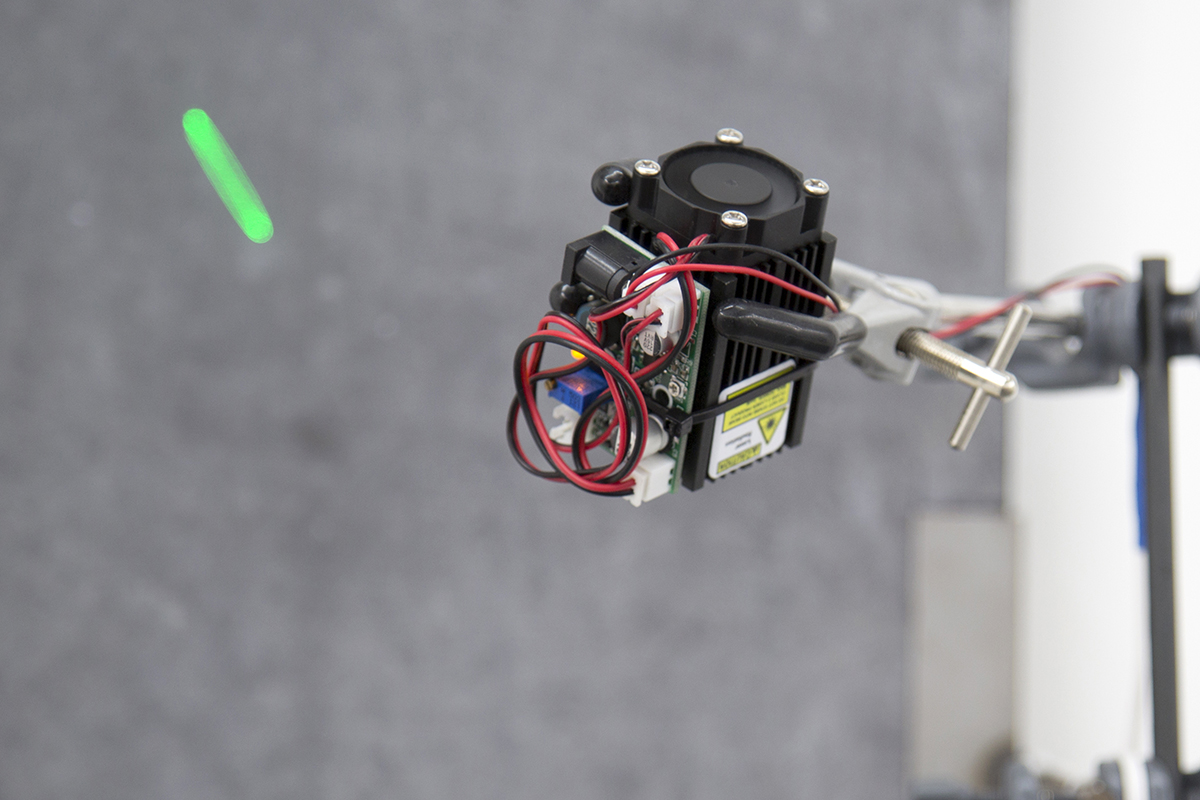

This technological alchemy, or technomancy, drives modern consumerism and weaves the Earth’s materiality with production, with 80% of the energy used in a computer’s lifespan is during the production phase. Microprocessors can also contain over 60 chemicals and minerals, which is only one component of 100s in devices such as mobile phones or computers. These are purely geological entities that stretch over timescales represented by both the future and the past while in your hand of the present. This process has created an (un)natural Ouroboros created by entangled copper network cables, a modern day life cycle to be melted down in the cultural foundry.

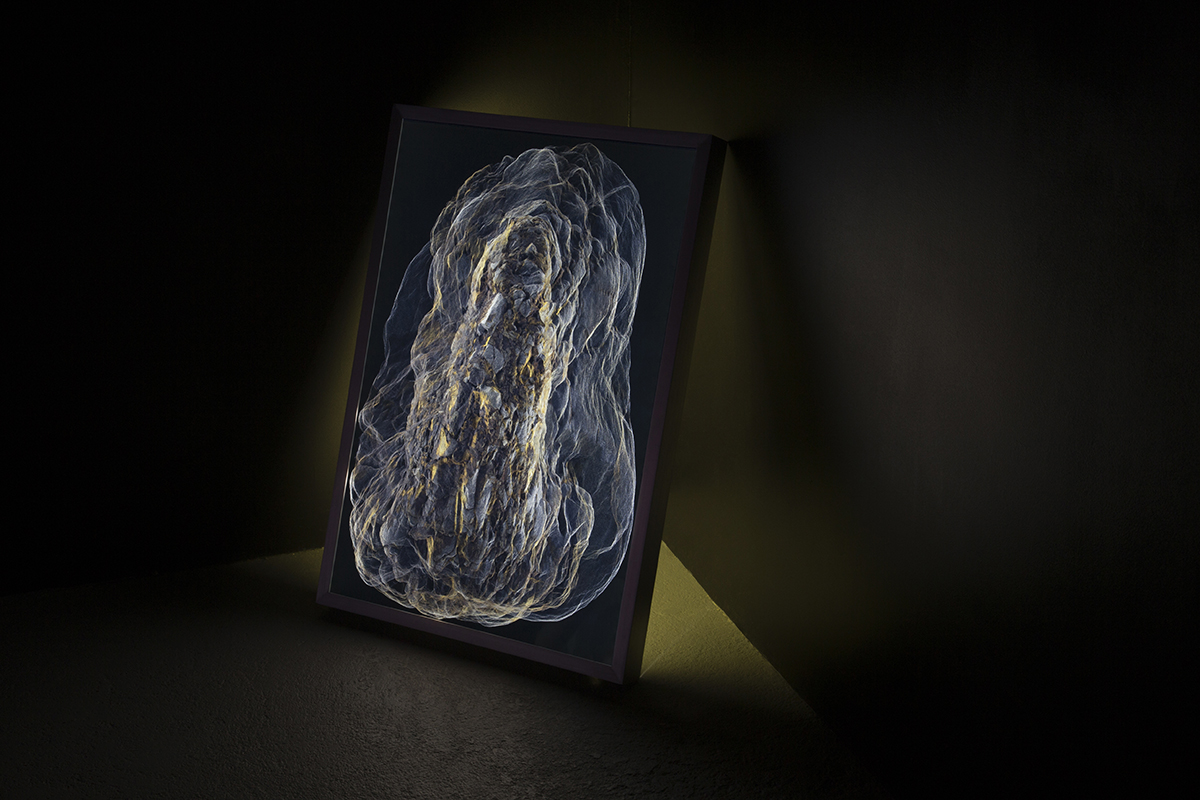

The foundry of techno-culture melts everything together to produce new alloys, a position that Deleuze and Guattari take through the idea of the metallurgical in A Thousand Plateaus. These metals have had a powerful position in the history of humanity through industry and technics which then transcends their existence across organic and inorganic planes. They argue that matter itself is not necessarily inert and that metals provide "the consciousness of matter-flow" or that "the non-organic life is the intuition of metallurgy". This becomes a new materialist argument designed to decenter anthropocentric thought and to open it up to the perspective of the nonhuman within the assimilation of technology and the natural world.

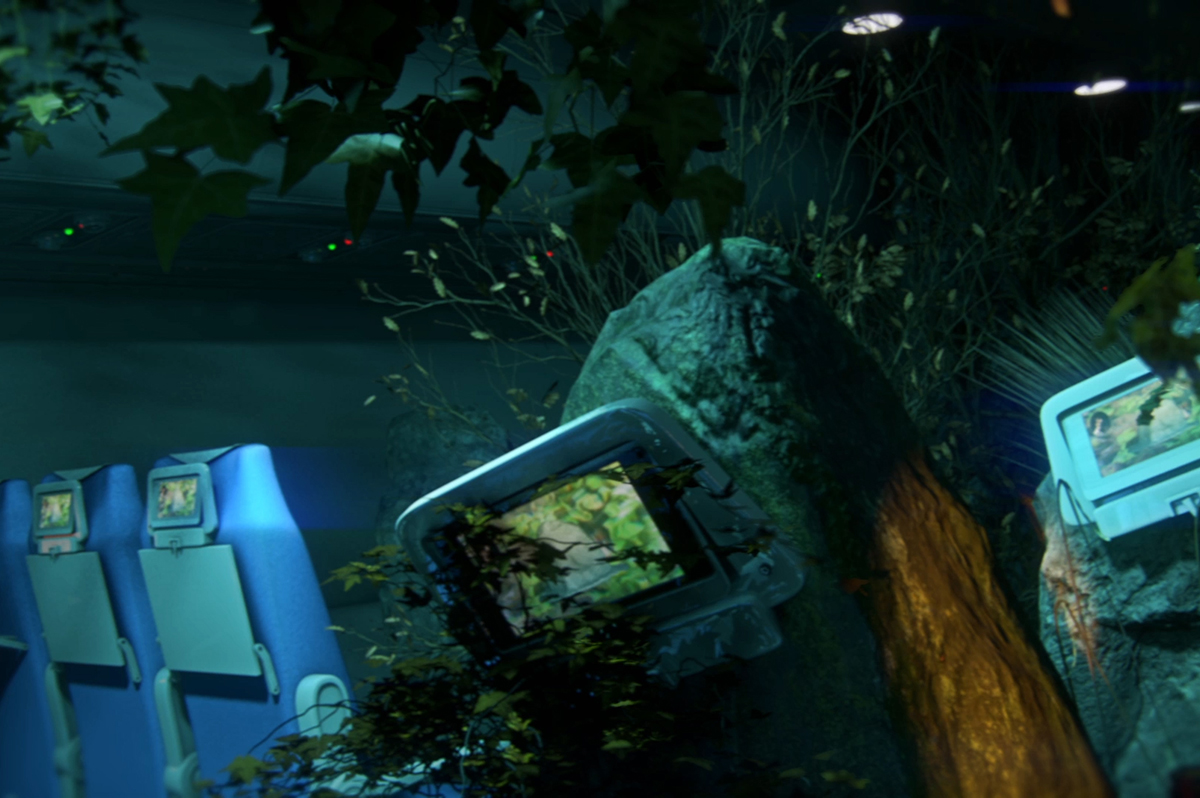

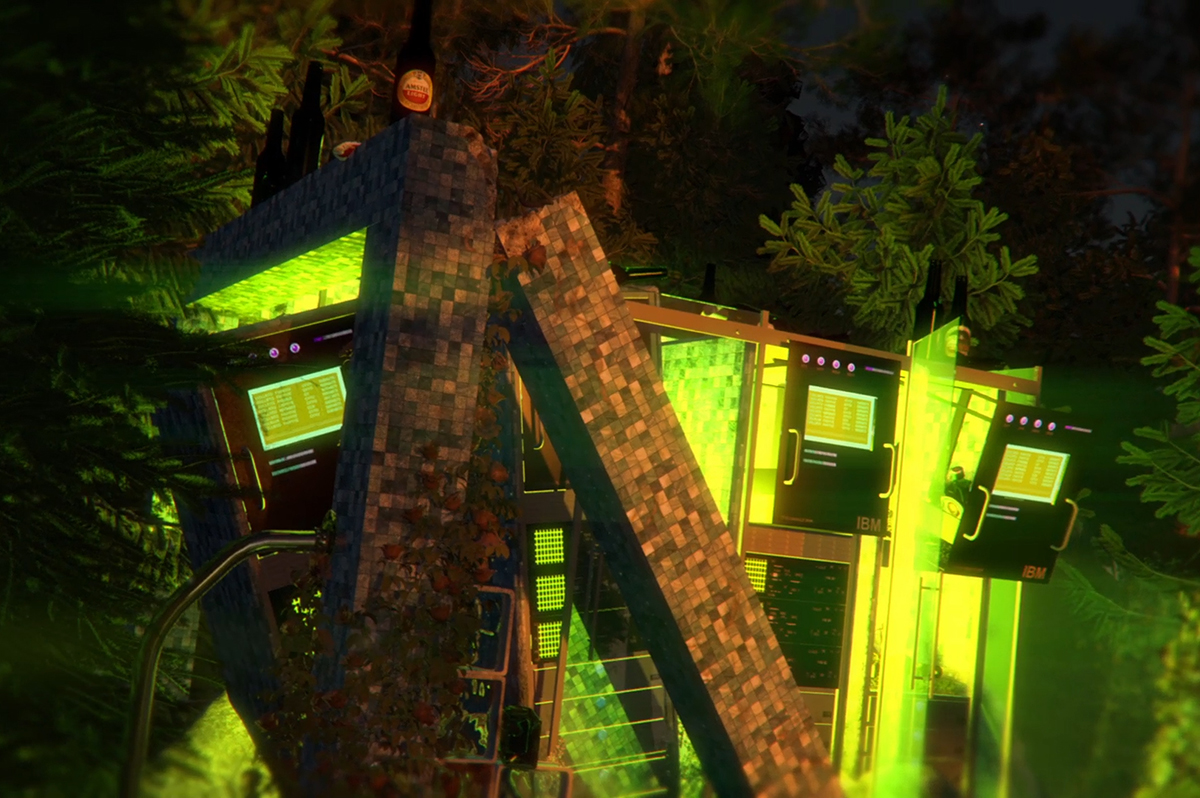

As the globalist economic ecosystem spreads right across the planet, the collateral damage from the loss of a big tech hardware company on the western stock markets tumbles down to the processor makers in Asia, then onto to the rare earth miners in parts of the Third World. The mine is the discovery point of the technological artifact and the corporate ground zero where human labour meets geological earth in a pit of filthy extortion. This extraction of geo-monetary value is mirrored in the new wave of cryptocurrency ‘mining’, with Bitcoin alone using more electricity than a country such as Ireland. Even in places of the world that do not adhere to such a capitalist agenda, its tentacles will be spreading nearby. It spreads to the ancient jungle tribe in the rainforest encroached upon by illegal loggers or the Inuit family living in remote regions of the arctic circle, watching pack ice melt faster than any of their ancestors have ever seen before.

The tentacles spread via growth systems that both capital and ecology share; the natural world loathes a vacuum and will immediately fill it with new life and the filling of this vacuum can easily be related to how Capital operates when always looking for the fabled ‘gap in the market’. Although the analogy to the natural world could obviously pertain to Capital being parasitic, the delicate symbiosis shares more with the biological commensalistic relationships, where one party takes more effect than the other. Nature is so effected by this relationship that some have deemed it the Capitalocene but it is now the only natural order of things we know.